In December 2017 Bitcoin values skyrocketed, peaking at the unprecedented amount of roughly US$19,000 per coin. Unsurprisingly, the market for cryptocurrencies exploded in response. Investors, companies, and even the public found a fresh interest in digital currencies. However, the exciting change in Bitcoin value did not just influence your average wealth seeker. It also influenced vast underground cybercriminal markets, malware developers, and cybercriminal behavior.

Blessing and Curse

The surge of Bitcoin popularity and price per coin piqued the interest of cybercriminals, driving cryptocurrency hijacking in the last quarter of 2017. However, the same popularity and price jump also created a headache for bad actors. Ransomware techniques and the buying and selling of goods became problematic. The volatility of the Bitcoin market makes ransom costs hard to predict at the time of infection and costs can surge upwards of $28 per transaction, complicating a criminal campaign. The volatility made mining, the act of using system resources to “mint” cryptocurrency, exceedingly difficult and raised transaction prices. This was especially true for Bitcoin, due its high hash rate of the network. (The higher the hash rate, the more people they compete against.)

Cybercriminals will always seek to combine the highest returns in the shortest time with the least risk. With the Bitcoin surge, malware developers and underground markets found themselves in need of more stability, prompting a switch to other currencies and a resurgence of old techniques.

It is far easier to mine small currencies because the hash rate is generally more manageable and hardware requirements can be more accessible depending on the network design. Monero, for example, is ASIC resistant, meaning that while mining specialized hardware does not have an overwhelming advantage to nonspecialized hardware. This allows the average computer to be more effective at the task. Due to this advantage, Monero is actively mined in mass by criminals using web-based miners on the machines of unsuspecting visitors. This intrusion is known as cryptojacking, which works by hijacking the browser session to use system resources. A quick look at recent examples of cryptojacking throws light on this issue. Starting mid-2017, there have been a slew of instances in which major websites have found themselves compromised and unwittingly hosting the code, turning their users into mining bots. The public Wi-Fi at a Starbucks outlet was found to hijack browsers to mine Monero. Even streaming services such as YouTube have been affected through infected ads. Ironically, Monero is said to be one of the most private cryptocurrencies. Attacks such as these have also happened on Bitcoin, NEM, and Ethereum.

Criminals are also leveraging techniques beyond mining, such as cryptocurrency address or wallet hijacking. For example, Evrial, a Trojan for sale on underground markets, watches the Windows clipboard and replaces any cryptocurrency wallet addresses with its own malicious address. Essentially, this hijacks a user’s intended payment address to redirect funds. Unwitting users could accidentally pay a bad actor, losing their coins with essentially no chance of recovery.

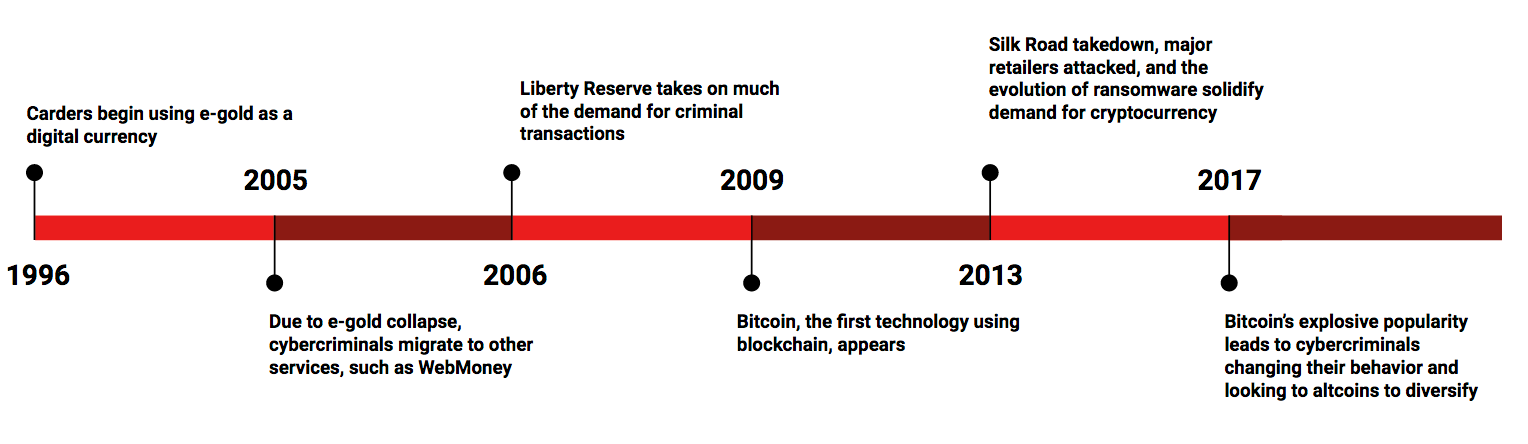

A Brief Timeline

Cybercriminals have always faced the difficulty of securing their profits from government eyes. For the cybercriminal, banks present risk. If a transfer is deemed illegal or fraudulent, the bank transfer can easily be traced and seized by the bank or law enforcement. Trading in traditional currencies requires dealing with highly regulated entities that have a strong motivation to follow the rules. Any suspicious activity on their systems could easily result in the seizure of funds. Cybercriminals have long tried to solve this problem using various digital currencies, the prelude to cryptocurrencies. When cryptocurrencies were introduced to the world, cybercriminals were quick to adapt. However, with this adoption came Trojans, botnets, and other hacker activities designed specifically for the new technology.

The evolution of digital currencies. Despite various attacks from bad actors, digital money continues to evolve.

1996: E-gold appeared, and quickly became popular with cybercriminals due to its lack of verification on accounts. This was certainly welcome among “carder groups” such as ShadowCrew, which trafficked in stolen credit cards and other financial accounts. However, with three million accounts, e-gold’s popularity among criminals also caused its demise: It was taken down just 10 years later by the FBI, even after attempts in 2005 to rein in criminal activity. Accounts were seized and the founder indicted, collapsing all e-gold operations.

2005: Needing another avenue after the collapse of e-gold, cybercriminals migrated to WebMoney, established in 1998. Unlike e-gold, WebMoney successfully discouraged the bulk of cybercriminals by modifying business practices to prevent illegal activities. This kept the organization alive but pushed many cybercriminals to find a new payment system.

2006: Liberty Reserve took on much of the burgeoning cybercriminal demand. The institution got off to a rocky start with cybercriminals due to the almost immediate arrest of its founders. The company’s assets were seized in 2013—causing an estimated $6 billion in lost criminal funds.

2009: Cybercriminals were increasingly desperate for a reliable and safe payment system. Enter Bitcoin, a decentralized, pseudo-anonymous payment system built on blockchain technology. With WebMoney usage growing increasingly difficult for cybercriminals and Liberty Reserve under scrutiny from world governments, cybercriminals required something new. Within the Bitcoin network, no central authority had the power to make decisions or otherwise seize funds. These protections against centralized seizures, as well as many of its anonymity features, were a major influence in the migration of cybercriminals to Bitcoin.

Game Changers

By 2013 cybercriminals had a vested interest in cryptocurrencies, primarily Bitcoin. Cryptocurrency-related malware was in full swing, as evidenced by increasingly sophisticated botnet miner kits such as BitBot. Large enterprises such as Silk Road, primarily a drug market, thrived on the backbone of cryptocurrency popularity. Then three major events dramatically changed the way cybercriminals operated.

Silk Road closed: The popular black market and first major modern cryptocurrency “dark net” market was shut down by the FBI. The market was tailored to drug sales, and the FBI takedown left its buyers and sellers without a place to sell their goods. The migration of buyers and sellers to less restrictive markets enabled cross-sales to a much larger audience than was previously available to cybercriminals. Buyers of drugs could now also buy stolen data—including Netflix accounts or credit cards—from new markets such as AlphaBay as demand increased.

Major retailers breached: Millions of credit card records were stolen and available, raising the demand for underground markets to buy and sell the data. Dark net markets already offering malware and other goods and services took up the load. Agora, Black Market Reloaded and, shortly thereafter, AlphaBay responded to that demand. Although many of these markets were scams, a few such as AlphaBay, which survived until its July 2017 takedown, were hugely successful. Through these markets, cybercriminals had access to a much larger audience and could benefit from centralized structures and advertising. The demand for other types of stolen data rose even more, particularly streaming media accounts and personally identifiable information, which carries a high financial return for cybercriminals.

In the past, many of the credit card records were sold on forums and other specialized carding sites, such as Rescator. The new supply of credit card data was so massive, however, that it enabled secondhand sales and migration into broader markets. Dark net markets were simply more scalable than forums, thus enabling their further growth. New players joining the game now had easy access to goods, stolen data, and customers. This shift reshaped and enabled retail targeting as it exists today.

Cryptocurrency-based ransomware introduced: Outside of dark net markets, malware developers sought to acquire cryptocurrencies. Prior to 2013 the primary method to maliciously acquire coin was through mining. Less effective methods included scams, such as TOR-clone sites, fake markets, or Trojans designed to steal private keys to wallets. By late 2013 malware developers and botnet owners sold their malware at a premium by including mining software alongside the usual items such as credit cards and password scrapers. However, at a cost of around $250 per coin, Bitcoin miners did not immediately see higher profits than they could manage with focused scraper malware. Criminals needed more reliable ways of acquiring coins.

Ransomware, a potentially lucrative form of malware, was already on the rise using other digital currencies. In late 2013, the major ransomware family CryptoLocker included a new option for ransomware victims—to pay via Bitcoin. The tactic effectively created a frenzy of copycat malware. Now malware developers could outpace the profits of scraper malware as well as secure currency for the underground market. Ransomware quickly enjoyed several immensely successful campaigns, many of which, including Locky and Samsa, are still popular. Open-source tools such as Hidden Tear allowed low-skilled players to enter the market and acquire cryptocurrencies through ransomware with only limited coding knowledge. The thriving model ransomware as a service emerged with TOX, sold via a TOR hidden service in 2015.

The use of cryptocurrencies by malicious actors has grown substantially since their inception in 2009. Cryptocurrencies meet a need and have been exploited in ever-evolving ways since their introduction. The influence of cryptocurrencies on underground markets, malware development, and attackers behavior cannot be understated. As markets change and adopt cryptocurrencies, we will surely see further responses from cybercriminals.